Better Brands 01: How Patagonia brought sustainability to the enlightened masses

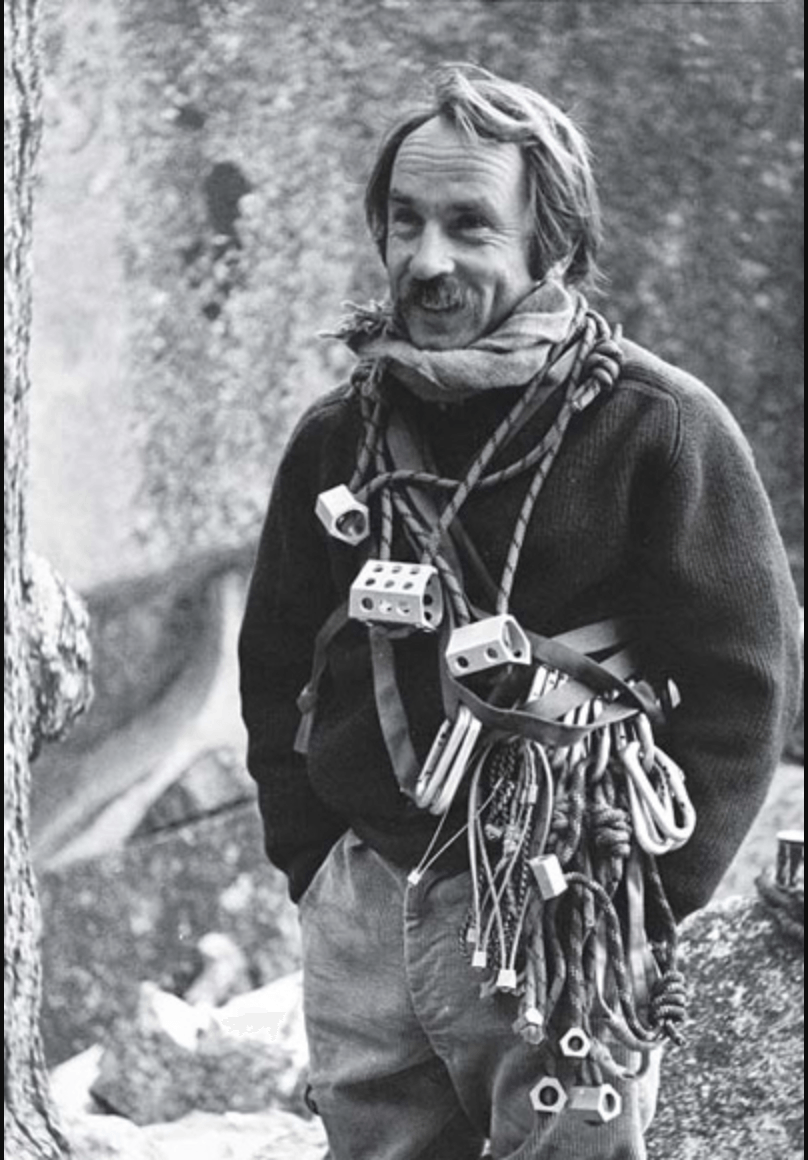

You could be forgiven for thinking that the Patagonia brand is a product of the naughties. In fact, the American retailer is almost 50 years old. Founded in 1973 by Yvon Chouinard, a rock climber who made his own climbing tools, the business now operates in 16 regions with an estimated annual revenue of $1b. Despite their long road to success, their team is relatively small, with an estimated 2,000 employees worldwide and their products sold in just 10 countries.

Patagonia grew at a modest pace throughout the eighties and nineties, with their popularity only really beginning to soar in the mid-2010s. This can be attributed to a number of factors, including the expansion of their product line, the appointment of a new CEO -Rose Marcario - and a number of outstanding sustainable marketing campaigns, including the launch of their ‘Worn Wear’ programme.

On the face of it, Patagonia is a company built from humble beginnings, and whilst their journey to renown has been slow and steady, they are now one of the first brands that come to mind when you think of ‘sustainable apparel’. And if you want to Google the South American region of the same name, you’ll be hard pressed to find it on the first page of Google. So let’s take a look at Patagonia (the brand), how they’ve achieved their market position, and the impact they have beyond the manufacture and distribution of clothing.

A Brief history of Patagonia

We mentioned that Yvon made his own climbing tools, and whilst that conjures images of a man at a lathe in his shed, the reality was something a little more entrepreneurial. Chouinard owned a coal-fired forge and was able to form Chouinard Equipment, a company which sold pistons, crampons and axes. Horrified by the news that his tools were causing significant damage to cracks within the rocks of Yosemite, Chouinard committed to a new approach of tool development and the practice of ‘clean climbing’.

Sadly, the business succumbed to bankruptcy to protect itself from a number of lawsuits. Ah, God bless America. But was ultimately bought by its employees through a process known as Chapter 11, reestablishing itself as Black Diamond Equipment, which still exists today.

These early years offer two key insights into Chouinard’s character. Firstly, he wanted to create products that were not only well-crafted and high quality, but were also sympathetic to the environment in which they were used. It’s also clear that he cared about his business on a cultural level, valuing his employees over profits and reputation – a mantra we see today in sustainable and regenerative businesses (ours and our clients’ included).

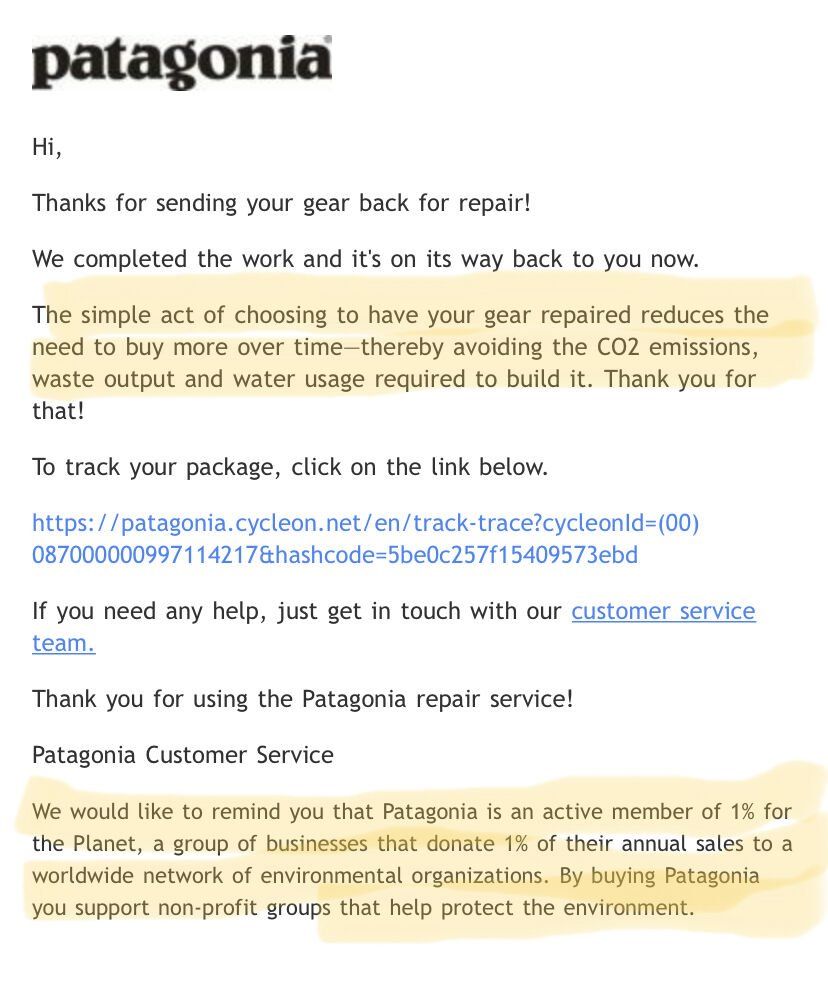

Patagonia’s formation was already well underway before the demise of Chouinard Equipment, and from the outset, Yvon made it clear that his new business was rooted in environmental activism and healthy living. By 1986, Patagonia had already committed 10% of all profits to ethical causes and local projects. If this sounds strangely familiar to the operating model of 1% for the Planet and its many member businesses, you may be surprised to know that Chouinard founded 1% for the Planet in 2002, with Patagonia being its first member.

Today, Patagonia’s product range is impressively broad, selling a wide collection of outdoor gear teetering on everyday fashion, including base layers, jackets, waders, skirts, hats, backpacks, waterproofs, and even baby-wear and beer. But Patagonia’s modern day success isn’t necessarily what they sell, it’s how they sell it.

Patagonia's Breakout Moment(s)

There’s no one key moment that led to Patagonia’s increased brand recognition, but their ‘leapfrog’ window can be narrowed down to 2015-17 when a number of changes to the business internally and externally lined up almost perfectly with a shift in consumer behaviour.

Let’s look at that wider landscape first. Responsible fashion or ethical brands certainly weren’t new in the mid ‘10s. A number of associations, such as Fair Trade, were already well-established vehicles to ensure more ethical prices, working conditions, and supply chains in companies around the world. And while brands like Lush and the Body Shop have been around for decades, they were still very much in the minority. It was rare to see a brand do much more than slap a green claim on the back of their packaging and call it a day. Patagonia was years ahead of those brands who were only just waking up to a world asking for better businesses.

Retailer,

Mr Porter, rather amusingly described Patagonia as “Kissing the lower lip of survivalist gear. It’s tactical wear for leisure scenarios, not doomsday.” Patagonia had managed to create a clothing line that can and will be used on a mountain range, at a surf competition, on a canoe trip or during a bungee jump, but it also wouldn’t look out of place on a Sunday afternoon trip to Waitrose. This is an interesting agility that few other brands have managed to straddle. The only present day example I can really think of is Under Armour, an uber-serious gym wear brand that I seem to see all too often on people who definitely are not at the gym.

Patagonia’s sincerity and history gave them the perfect springboard to position themselves at the forefront of the new sustainable fashion movement. Not only that, they were a brand ready to put their money where their mouth is. 2017’s ‘Worn Wear’ launch gave customers the opportunity to return well-worn merchandise in exchange for credits, with the used items being laundered, repaired and resold online.

The company then built on the success of Worn Wear and launched ReCrafted, an outlet that sells clothing made from scraps of used Patagonia gear. This is a model we’ve seen echoed by startups that are closer to home, such as Rapanui, based on the Isle of Wight. More recently, Patagonia launched a free repair service that promises to fix items that have been damaged or are just looking a little old. The only cost to the customer is postage.

Rose Marcario, who we mentioned earlier, saw profits rise by 300% during her 12 year tenure at the business. Her legacy includes on-site childcare, a strict evaluation of Patagonia’s entire production process, and a stringent waste audit. Marcario was not afraid to speak out, and often criticised Trump’s administration and their wilful ignorance on climate change. During 2016’s US Election, she closed Patagonia’s store to raise awareness of the importance of voting. Stepping down in 2020, she left behind an entirely transformed organisation – an agile, efficient business leading the way in sustainability, ethical supply chains and hard and fast activism.

How is the Patagonia product different?

Step into a Patagonia store or visit their website, and you won’t be struck by big, bold colours, titillating taglines or lavish logos. The brand is simple, muted and straightforward – well-designed daily wear that favours materials and functionality over hype and trendy exposed hems.

Patagonia’s products are generally made from a high percentage of recycled materials, and an impressive 83% of their entire product line is Fair Trade Certified. A number of trademarked technical features include moisture wicking and odour control – useful for reducing spins around the washing machine.

Despite their extensive catalogue, the story is very much the same with each and every product. The cut of the garment is sympathetic to its use case, the logo is low-key and minimal, and there’s a clear and obvious ‘impact path’ which you can follow, from country of manufacture to an item’s individual components.

Their approach to quality from a technical and practical level is a guarantee that a t-shirt isn’t going to start falling apart a few weeks after you’ve bought it. And in part, this is why their free repair service works and isn’t a loss leader.

Patagonia has achieved a balance between several consumer movements: the outdoorsy type in need of robust and reliable gear, the environmentally-conscious type who cares about who made it and how it’s made, and the activist, who wants to see a new breed of big brands who can drive positive influence amongst their customer base. Perhaps their ideal customer is all three of these things.

When you’re walking behind someone in a Patagonia t-shirt, you’re not quite sure if they’re off to scale Everest, to sit in a coffee shop, or to march with Extinction Rebellion. If that was my brand, that would be something I’m proud about.

Campaign focus: Don't buy this jacket

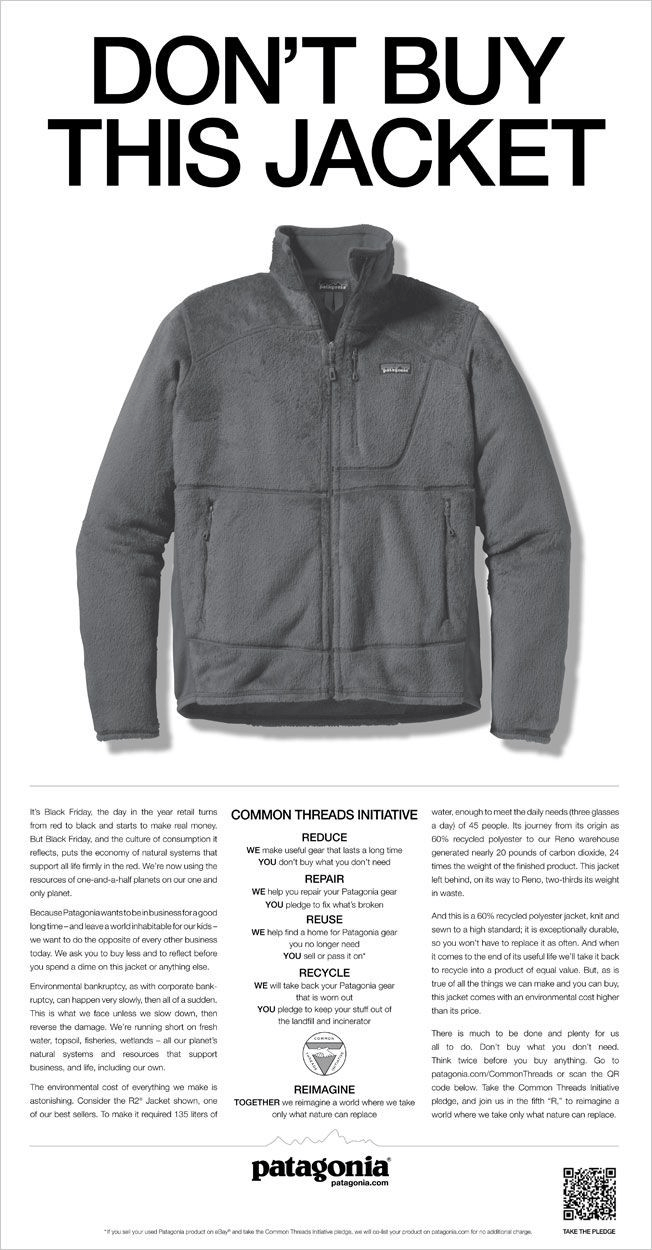

In 2011, a full-page ad in the New York Times exclaimed “DON’T BUY THIS JACKET”. Patagonia wasn't holding back in their attack on rampant consumerism. But what’s the angle here? Buy better and buy less? Well, kind of. The ad was published on Black Friday, which was no coincidence. The copy—six long paragraphs laid out in an editorial format—broke down exactly what it takes to make the jacket shown in the photograph. Despite Patagonia’s ethical approach to manufacturing, it still used a staggering 135 litres of water per garment.

The overarching theme was a clear message to invest in better quality garments that last, and to treat those garments well, rather than an item that needs changing or throwing out on a whim within a few months.

They risked coming across as a cash-rich, preachy, holier than thou conglomerate, but they pacified any naysayers by admitting up-front that garment manufacture is, by nature, resource-heavy. And they appease this with their clear and encouraging message to be a better consumer, or better still, a lesser consumer.

The ‘Don’t Buy This Jacket’ campaign has been referenced, referred to, and written about countless times since its publication, and has remained an iconic campaign in the intervening decade.

Patagonia’s extra efforts

Away from the press and the products, what does Patagonia do to offset the inevitable footprint that a company of their size leaves on the planet? Well, they do a lot. In fact, their global website puts ‘Activism’ second in their four-item menu, and leads visitors to a page rich with resources, efforts, promises, and programmes. There’s perhaps too many to list here, but here are a number of standout efforts:

- Patagonia Action Works: a directory of over 1,400 global grantees that you can donate to

- 1% for the Planet, Patagonia’s own self-imposed ‘Earth tax’, which many other businesses have now joined

- Global Sports Activists: high profile sports people using their roles to drive social change

The brand also uses its voice to speak out on several social issues, including its public boycott of the Outdoor Retailer Trade Show, pledging $1m to Black Votes Matter, and even suing the US government and Trump over their handling of the Bears Ears National Monument protected land.

In July 2020, Patagonia pulled all of their ads from Facebook in protests against the social media platform doing little against hate speech throughout its public network. This was part of a wider ‘Stop Hate for Profit’ campaign.

In conclusion: Patagonia’s purpose

If you’ve got this far and aren’t impressed by Patagonia’s long and lively journey, then what the hell’s wrong with you? On an aesthetic level, the brand isn’t for everyone. But when you consider their origin story and their resistance to sell out or, well, sell crap, it’s an incredibly impressive organisation that is certainly putting about as much as it can back into the world.

It can be difficult to comprehend how a business of their size can start to be regenerative. After all, if we removed all traces of Patagonia from the world tomorrow, would we see a greener planet? Perhaps – their carbon footprint wouldn’t be missed, but just think what it might be replaced with.

Brands like Patagonia set a new standard. They ‘territorialise’ an area of the fashion industry and divert customer spending that would have otherwise made its way into fast fashion, unsustainable supply chains and unethical practices.

When you buy a product from Patagonia, you receive a product that is practical, functional and well-made, whilst funding projects, programmes and efforts that are noticeably improving the lives of others, whether that’s a climate anxiety workshop in central London or influencing environmental policy in Buenos Aires.

The Avery & Brown Better Brand Score:

Sincerity: ★★★★☆

Marketing: ★★★★☆

Design: ★★★★☆

Leadership: ★★★★★

Employer brand: ★★★★★

Overall score:

4.4 out of 5

Keep an eye open for Better Brands 02, where we’ll be looking at Ben & Jerry’s. I wonder if you can send a tired, old B&J carton back to them and get it refilled with delicious ice cream for just the cost of postage? Wishful thinking, perhaps. See you soon.

Share the love